Language is at the heart of what makes us human. It is universal, cutting across societies and cultures, and yet profoundly diverse in its expressions. No language is inherently superior to another, regardless of its perceived prestige, historical prominence, or global reach. Every language, whether spoken or signed, carries unique ways of understanding the world and reveals different facets of human life.

The Myth of Linguistic Superiority

Historically, dominant languages such as English, Latin, Arabic, and Mandarin have often been viewed as “superior” due to their widespread use, standardization, or association with political or religious power. But this perception is tied more to the status of their speakers than to any intrinsic qualities of the languages themselves. Every language, even unwritten and unstandardized ones, is fully equipped to meet its speakers’ communicative needs.

Languages differ not in their capacity to express ideas but in the specific features they emphasize. For example, while some languages excel in describing kinship relations or the natural world, others have unique ways of conveying abstract concepts or emotions. Linguist Roman Jakobson famously noted, “Languages differ essentially in what they must convey and not in what they may convey.” This means that while all languages are capable of expressing the same ideas, the way they structure and prioritize those ideas varies.

The Scale of Language Endangerment

Despite the equality of languages in a linguistic sense, the social and historical contexts of their speakers vary drastically. Around 50% of the world’s 7,000 languages are spoken by communities of 10,000 people or fewer, with hundreds having fewer than 10 speakers left. This isn’t a natural phenomenon—it’s a crisis caused by historical and contemporary pressures, including colonization, urbanization, and globalization.

Languages aren’t disappearing because they are inadequate. They’re being pushed out of existence by dominant languages backed by economic and political power. In the U.S., for instance, half of the 300 Indigenous languages once spoken have already been silenced. Most of the remaining ones are severely endangered, spoken only by a few elders. The same pattern is visible in Australia, where nearly all Aboriginal languages are critically endangered, with only a few still being actively passed down to children.

Why Linguistic Diversity Matters

The loss of a language isn’t just a cultural tragedy—it’s a profound blow to human knowledge. Many endangered languages carry insights that would otherwise be lost. For example:

- The Khoisan languages of southern Africa reveal the extensive use of click sounds in human communication.

- Warao, spoken in parts of South America, shows us an entirely different way to order sentences (object-subject-verb).

- Hmong-Mien languages of Southeast Asia demonstrate the possibility of using up to a dozen tones to distinguish meaning.

But languages don’t just encode abstract knowledge. They also carry oral histories, local ecological wisdom, poetry, humor, and deeply embedded cultural practices. When a language dies, much of this information becomes inaccessible, even to those who translate its words into other languages.

Language Loss and Well-Being

The disappearance of a language has direct consequences for the physical and mental health of its speakers. Studies show that maintaining one’s mother tongue is essential for well-being, particularly among Indigenous and minority communities.

The Forces Behind Language Loss

The disappearance of languages isn’t happening by chance. It’s driven by systemic pressures, including:

- Colonization and imperialism, which impose dominant languages at the expense of local ones.

- Urbanization, where smaller languages are abandoned in favor of metropolitan ones.

- Economic incentives, as families prioritize dominant languages like English or Mandarin for their children’s education and job prospects.

Today, a small number of “killer languages” like English, Spanish, and Chinese dominate global communication. These languages expand through political and economic power, leaving smaller languages with fewer opportunities for survival.

The Role of Monolingualism

Monolingualism, particularly among dominant-language speakers, contributes to the erosion of linguistic diversity. In English-speaking countries, for instance, monolinguals often fail to appreciate the value of other languages. Many don’t realize that a multilingual upbringing is a significant cognitive advantage, fostering empathy and cultural understanding.

For monolinguals, learning another language—even at a basic level—can challenge ingrained biases and offer a new perspective on the world. Yet, the privilege of speaking a dominant language often blinds people to the need for multilingual efforts.

Language Revitalization: A Global Movement

Around the world, hundreds of language revitalization movements have emerged, driven by a desire to preserve cultural heritage and linguistic diversity. These efforts face enormous challenges, as creating even a single new speaker of a critically endangered language can take years of work. Yet there are glimmers of hope:

- Scattered speakers of endangered languages are connecting online, creating virtual spaces for language learning and cultural exchange.

- Advancements in artificial intelligence and augmented reality offer new tools for documenting and teaching endangered languages.

Still, revitalization efforts require real support—financial, political, and technical—from majority populations. Without this backing, language activists face stigma, indifference, and a lack of resources.

What Can Be Done?

For dominant-language speakers, the first step is awareness. Understanding the privilege of speaking a dominant language and learning about endangered languages are crucial. Linguists and activists are working to document and preserve as much as they can, creating dictionaries, grammars, and recorded texts for posterity.

However, true preservation depends on communities deciding to continue speaking their languages. This requires creating meaningful opportunities for using endangered languages in everyday life, from education to media to community events.

Conclusion

Languages are more than a means of communication—they are living systems of knowledge, identity, and culture. Their loss represents not just the disappearance of words but the erasure of unique ways of understanding the world. By valuing and supporting linguistic diversity, we can help ensure that the richness of human expression endures for generations to come.

The Fight to Preserve Endangered Languages: A Case for Cherokee and Beyond

Tom Belt, a Cherokee native from Oklahoma, didn’t encounter the English language until kindergarten. Cherokee was the only language spoken in his home, and it shaped his early life and identity. After college, he traveled the country as part of the rodeo circuit, eventually settling in North Carolina to reconnect with a woman he had met two decades earlier.

“My wife told me years ago that she was drawn to me because I was the youngest Cherokee she knew who could still speak the language,” he recalls. What started as a visit turned into a permanent move, and the two married.

A Community Without Its Language

Though his wife was also Cherokee, she didn’t speak the language. Belt soon realized he was a minority among his own people. By the time he arrived in North Carolina, only 400 people in the Eastern Band of Cherokee—a tribe living in their ancestral homeland—could speak the language fluently. Even worse, Cherokee wasn’t being passed down to children.

“I began to understand how serious the situation was,” Belt explains. He decided to take action.

A Global Crisis of Language Loss

Cherokee is far from the only endangered language. Over the past century, approximately 400 languages have gone extinct, averaging one every three months. Linguists estimate that 50% of the world’s 6,500 languages will disappear by the end of this century, with some even projecting up to 90%.

Currently, the top 10 languages globally are spoken by about half of the world’s population. Meanwhile, hundreds of languages teeter on the brink of extinction, with only a handful of speakers left. These range from Ainu in Japan to Yagán in Chile, and finding speakers can be a monumental challenge. For instance, Alaska’s Eyak language vanished in 2008 when its last speaker, Marie Smith Jones, passed away.

“That’s How Languages Die”

The fewer speakers a language has, the harder it is to sustain or even document it. As David Harrison, co-founder of the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages, points out, many endangered languages are spoken by isolated individuals or scattered groups. In extreme cases, speakers refuse to communicate with one another, as seen with Ayapaneco in Mexico, where the last two fluent speakers avoided speaking to each other for years.

Even when speakers use their native language, lack of regular practice can erode fluency. Salikoko Mufwene, a linguist from the University of Chicago, grew up speaking Kiyansi, a small language in the Democratic Republic of Congo. After decades away, he noticed his fluency deteriorating during a visit to his hometown. “I realized that Kiyansi exists more in my imagination than in my daily practice,” he says. “That’s how languages die.”

The Pressures Driving Language Loss

Languages often decline when displaced by more dominant ones with greater social, political, or economic power. In such scenarios, learning dominant languages like English, Mandarin, or Swahili becomes crucial for accessing education, jobs, and opportunities.

Immigrant communities, in particular, often prioritize teaching dominant languages to their children, fearing that retaining their heritage language might hinder their success. Compounding this, speakers of minority languages have historically faced persecution.

For instance, throughout the 20th century, Native American children in the U.S. and Canada were sent to boarding schools where they were forbidden to speak their mother tongues. Similarly, English-speaking Americans have often shown hostility toward non-English speakers, especially Hispanics.

Persecution persists in modern times. In 2021, a linguist in China was arrested for trying to establish schools teaching the Uyghur language. He has not been heard from since.

A Grim Landscape for Endangered Languages

UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger lists 576 languages as critically endangered, with thousands more classified as endangered or vulnerable. The Americas are particularly affected, with nearly all minority languages in the U.S. and Canada under threat. Even Navajo, with thousands of speakers, is endangered due to the dwindling number of children learning it.

Australia holds the grim distinction of having the highest proportion of endangered languages. Of the 300 Aboriginal languages spoken when Europeans arrived, 100 have already disappeared. Linguists estimate that 95% of the remaining ones are on the brink of extinction, with only about a dozen still taught to children.

Why Does It Matter?

Some argue that language loss is a natural consequence of societal evolution, much like the extinction of species. However, many linguists and anthropologists strongly disagree.

“Languages are fundamental to humanity’s heritage,” says Mark Turin, a linguist at Yale University. Language is often the sole means of transmitting cultural traditions, oral histories, and knowledge. Before they were written, iconic works like The Iliad and The Odyssey were oral narratives passed down through generations.

“How many traditions have already disappeared because no one recorded the language in which they were told?” Turin asks.

Unique Cultural Insights

Languages also encode distinct worldviews. For instance, Cherokee doesn’t have a word for “goodbye.” Instead, speakers say, “I’ll see you again.” Similarly, there’s no direct equivalent for “I’m sorry,” but the language includes unique expressions like oo-kah-huh-sdee, which conveys the joyful feeling evoked by seeing something adorable, like a baby or kitten.

“Languages convey specific ways of interpreting human behavior and emotions that English doesn’t,” Belt explains. Without language, an entire culture can falter—or disappear altogether.

A Wealth of Knowledge

Languages also preserve vast reservoirs of knowledge about the natural world. Cherokee, for instance, has names for every berry, plant, and mushroom in the Appalachian Mountains, along with details about their uses—whether they’re edible, poisonous, or medicinal.

“No culture has a monopoly on human genius,” says Harrison. “When languages disappear, we lose ancient knowledge that could still be of use today.”

The Challenge of Revitalization

Efforts to revitalize endangered languages often start with documentation. Linguists work to create dictionaries, record oral histories, and archive traditions. However, without active speakers, these efforts can feel like preserving artifacts in a museum.

For the Cherokee Eastern Band, revitalization efforts have included immersion schools where children are taught core subjects like math and science in Cherokee. The language is also now taught at the local university, where Belt serves as an instructor.

Thanks to these initiatives, about 60 children in the Eastern Band can now speak Cherokee—an improvement over the dire situation Belt encountered in 1991.

The Role of Technology

Technology is playing an increasing role in language preservation. For example, Cherokee speakers can now use a version of Windows 8 in their language and access apps that allow texting in Cherokee’s 85-character script. Online platforms like Digital Himalayas and Enduring Voices connect speakers of endangered languages and provide tools for learning.

A Long Road Ahead

Despite progress, revitalizing a language remains a steep uphill battle. As one elder told Belt: “It’s great that you want to do this, but remember—they didn’t take it away overnight, and you won’t bring it back overnight.”

Efforts like those of the Cherokee Eastern Band serve as a beacon of hope for other endangered languages worldwide. While the challenges are immense, the fight to preserve linguistic diversity is crucial—not just for the communities involved but for the wealth of knowledge, culture, and humanity it represents.

The Impact of English on Indigenous Languages in the 21st Century

The linguistic landscape of the 21st century is defined by the intersection of English’s global dominance and the resilience of indigenous languages. For Generation Z, this interplay unfolds in a context where English increasingly serves as a tool for communication, education, and digital interactions. While English facilitates global connectivity, its pervasive influence raises critical concerns about the survival of indigenous languages and cultural diversity.

English as a Global Lingua Franca

English has become the world’s lingua franca, transcending borders and influencing nearly every domain, from technology and commerce to academia. Its role as the dominant language in digital communication amplifies its reach, particularly among Gen Z, who navigate a world saturated with English-centric social media and internet content. David Crystal’s research in Language and the Internet (2001) highlights how English has evolved into the de facto language of the digital age, shaping the linguistic preferences and practices of users worldwide.

This global reach, however, contrasts sharply with the situation of indigenous languages. Languages like Santali, Khasi, and Konkani in India, or Tulu and Manipuri, reflect the rich diversity of human expression but face significant pressure from English in both digital and offline spaces. Urbanization, globalization, and the prioritization of English over native languages contribute to this decline.

English in Education and the Marginalization of Native Languages

The dominance of English in education systems worldwide has profound implications for indigenous languages. Skutnabb-Kangas (2000) identifies a trend in which English is prioritized as the medium of instruction, often at the expense of local languages. In India, this is particularly evident as regional languages struggle for survival in schools that favor English-medium education.

For example, Kannada in Karnataka, Tamil in Tamil Nadu, and Assamese in Assam are seeing their roles diminished in favor of English, which is often perceived as a gateway to economic opportunities. The marginalization of these languages in formal education results in the erosion of cultural heritage and community identity. This trend is not unique to India; similar patterns are observed in indigenous communities in Australia and North America, where native languages are overshadowed by English-centric curricula.

English Dominance in Digital Media

The digital realm is another area where English exerts significant influence. Social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter are predominantly English-oriented, shaping language preferences among younger generations. This has far-reaching consequences for native languages, as English-centric content often relegates regional languages to the background.

Blommaert’s concept of linguistic hegemony (2010) explains how English dominates digital spaces, creating linguistic hierarchies that disadvantage indigenous languages. While some Gen Z users engage in hybrid language practices, such as code-switching between English and their native tongues, the overall trend points to the growing normalization of English as the default language online.

The Threat to Linguistic Diversity

The increasing dominance of English contributes to the gradual homogenization of linguistic diversity. Warschauer and Matuchniak argue that the emphasis on English in digital environments diverts resources and attention from initiatives aimed at preserving indigenous languages. As these languages lose visibility and representation, their cultural significance and unique knowledge systems are at risk of being lost.

Case Studies: The Struggle of Native Languages in India

India, with its unparalleled linguistic diversity, provides a compelling backdrop to examine the challenges faced by native languages.

- Kannada in Karnataka: Despite being the state’s official language, Kannada is increasingly sidelined by English in commerce, education, and digital media.

- Tamil in Tamil Nadu: Known for its strong language tradition, Tamil is under pressure from the rise of English-medium schools, which are perceived as offering better opportunities.

- Assamese in Assam: In this bilingual state, English often takes precedence over Assamese, particularly in urban areas, threatening the continued use of the local language.

- Marathi in Maharashtra: Urbanization and the popularity of English-medium education challenge the vitality of Marathi, despite its official status.

- Khasi in Meghalaya: English-centric education systems have reduced the use of Khasi, impacting the cultural identity of its speakers.

These examples demonstrate how English’s rise as a dominant language undermines the survival of regional languages, which are integral to India’s cultural fabric.

Promoting Multilingualism: The Path Forward

To counter the erosion of linguistic diversity, efforts must focus on fostering multilingualism and protecting indigenous languages. Several initiatives offer hope:

- UNESCO’s Role: Programs like “Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education” emphasize the importance of using native languages in education. This approach recognizes the connection between language and culture and ensures that indigenous knowledge systems are preserved.

- Grassroots Language Revitalization: Community-driven initiatives, such as Zuckermann’s Barngarla revival in Australia, demonstrate how local efforts can resuscitate endangered languages and restore cultural identity.

- Technology as an Ally: Digital tools and platforms can support language preservation. Projects like the Rosetta Project and Google’s Translate Community offer resources for documenting and promoting linguistic diversity. Machine translation systems designed with inclusivity in mind can bridge linguistic divides without diminishing the importance of individual languages.

- Inclusive Education Policies: Policies that promote multilingual education, such as those adopted in post-apartheid South Africa, highlight the value of linguistic diversity in fostering social cohesion.

English and Global Citizenship

While English provides a means of global communication, it is essential to balance its dominance with efforts to maintain linguistic diversity. Bilingualism and multilingualism foster understanding and empathy across cultures, enriching the social fabric of communities. Recognizing the value of native languages as carriers of culture and knowledge is critical for preserving humanity’s collective heritage.

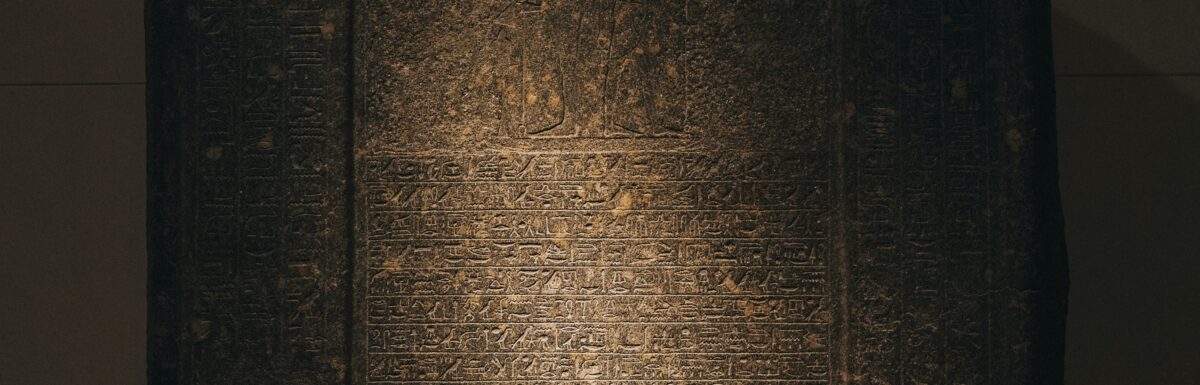

Foto de Andrea de Santis.

Leave a Reply